By Scott Waide

Samap village in Papua New Guinea’s East Sepik province

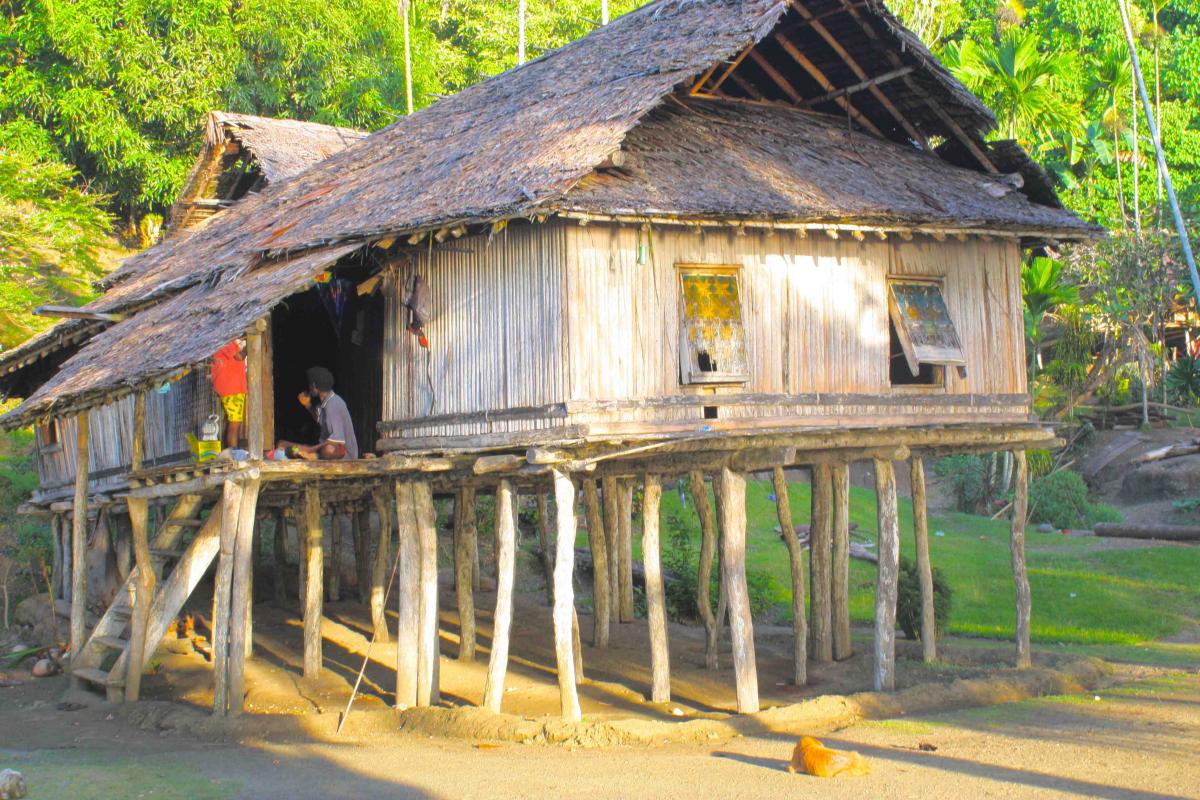

is like many other places in in the country - isolated and without road access. It lies in a tiny secluded bay facing the Bismarck Sea. The village houses stand on ancient rickety posts bearing withering sago thatch roofs.

A group of women and children stand on the shore as a fleet of nine fiberglass dinghies each powered by relatively new 40-horse power Yamaha engines come into the bay. Apart from a few men on each of the boats, all are void of any large cargo.

The community’s isolation masks a transformation that has been happening over the last three years, a transformation driven by a small group of businessmen on a path to becoming self-made millionaires.

The men are returning from Madang. It’s a trip that has just earned the community more than 12 thousand dollars from the sale of buai or betelnut – the fruit of the acacia palm used traditionally chewed during social gatherings.

Each month, they earn an average of 40 thousand dollars which translates to a gross annual income of more than 400 thousand dollars which is shared amongst the members of the community depending on how much work they contributed.

“There are local buyers who buy buai from people in the village,” says Robert Mandu, the ward councilor who made about 6 thousand dollars today. “We pack them in bags and sell it to Seti a businessmen who comes from the Highlands.”

Those actively involved in the buai trade say it’s not just about business and making money. They’re building on extended family relationships and supporting their clansmen and women in improving their standard of living. Robert from the Sepik and Seti from the Highlands aren’t related by blood but they drew on the strengths inherent in both their cultures and reached out to others.

Every decision is made collectively with their elders. Robert consults with other members of his family. Seti is always accompanied by an older uncle who helps him buy the buai. The trading happens at the small village of Kosakosa on the Madang - East Sepik border where Robert’s sister lives with her husband.

Over three years, Seti and Robert’s families developed this once tiny local trade confined to village consumers into an industry that will be worth over a million dollars over the next 5 years. The trade spans six provinces and links coastal buai growers in Samap to the vast market of more than a million consumers in the highlands of Papua New Guinea.

The venture began with Henry – Robert’s older brother – who started off by selling Buai using small 25 horsepower Yamaha engine. Henry is a man of few words and doesn’t readily take credit for the success of Samap’s growing band of young entrepreneurs. But everyone knows his actions speak volumes. For many in Samap, Henry is a visionary.

These days, there is very little haggling over prices. The buyers and sellers agree on a price that is beneficial to both families. Seti then makes direct deposits of up to 15 thousand dollars for every order into the bank accounts managed by Robert. Each seller knows how much he or she will get per bag and how much is being deposited. The boat owners are also paid for the hire of their boats upfront. Nobody is cheated.

Theirs is a relationship based on trust and constant communication. No lawyers. No overseas consultants. No written agreements. It’s an arrangement that is working with little trouble.

“We’ve bought 10 boats from our buai sales,” says Robert. “We are working to get a few more.

“We are in control of our own economic development. We are deciding what we want to do and how much money we want to make”

The Buai trade isn’t their only income source. Every week, a boat goes to the East Sepik Provincial capital of Wewak loaded with bags of dried cocoa beans. This is another community effort that brings in a collective income of up to 1500 dollars a week.

“We used to sell unprocessed cocoa beans to buyers from other villages,” Robert says. “Many of us aren’t well educated and we knew very little about cocoa prices and we used to get cheated a lot.”

Led by Henry, the people of Samap, sought the expertise of a relative who built them a cocoa fermentery. This reduced the weight they had to carry into town and increased the value of their product.

What the people of Samap are doing is in vast contrast to those in the nearby villages of Kaup and Tiring where Malaysian loggers are clear felling large areas of rainforest. They’ve been promised oil palm development as well as benefits under a special agriculture business lease (SABL), which is currently the focus of an investigation. So far, there’s no hint of progress and they’re still waiting for that “development.

“We kicked those loggers off our land. They drove their bulldozers into a wildlife management area that our fathers established,” Robert says. “But the people of Kaup and Tiring have taken what we rejected. We told them but they haven’t listened.”

After more than three decades since the Australian colonial administration left, Samap is still without a road link to the provincial capital of Wewak. The road ends at the nearest mission station of Turubu, which is a day’s walk from Samap. Malaysian loggers are pressuring leaders of Samap to sign logging agreements that come with the promise of a road link.

“Those Malaysians haven’t learned and still think we’re dumb!” says an amused Samap elder. “How can you build a road with 500 thousand kina? We know they only want the trees.

“Besides, what would we need a road for? We already have what we need.”

As the Local Level Government Councilor, Robert is the man responsible for the implementation of government policy. But he gets no support from the provincial or national governments and he doesn’t get paid. Yet it doesn’t bother him.

“We don’t need government handouts. We don’t need employment provided by a logging company. We’re making more money on our own.”

The important thing for them is that they are in control and they can choose what they want. Next month, Robert and his brothers will buy a sawmill. This will help his community build new houses for themselves from timber harvested from their land.

“The next time you come, these houses will be gone. We will have posts made of sawn timber and houses that have corrugated iron roofs. People deserve to live in good houses.”

- Klaireh's blog

- Log in to post comments

Comments

This is wonderful. Well done to the people of Samap for being

This is wonderful. Well done to the people of Samap for being self sustainable and telling those greedy damaging loggers where to go. I am proud of you all and the unwavering level of passion and determination you not only have for your peoples standard of living, but also for your beautiful forest and environment..